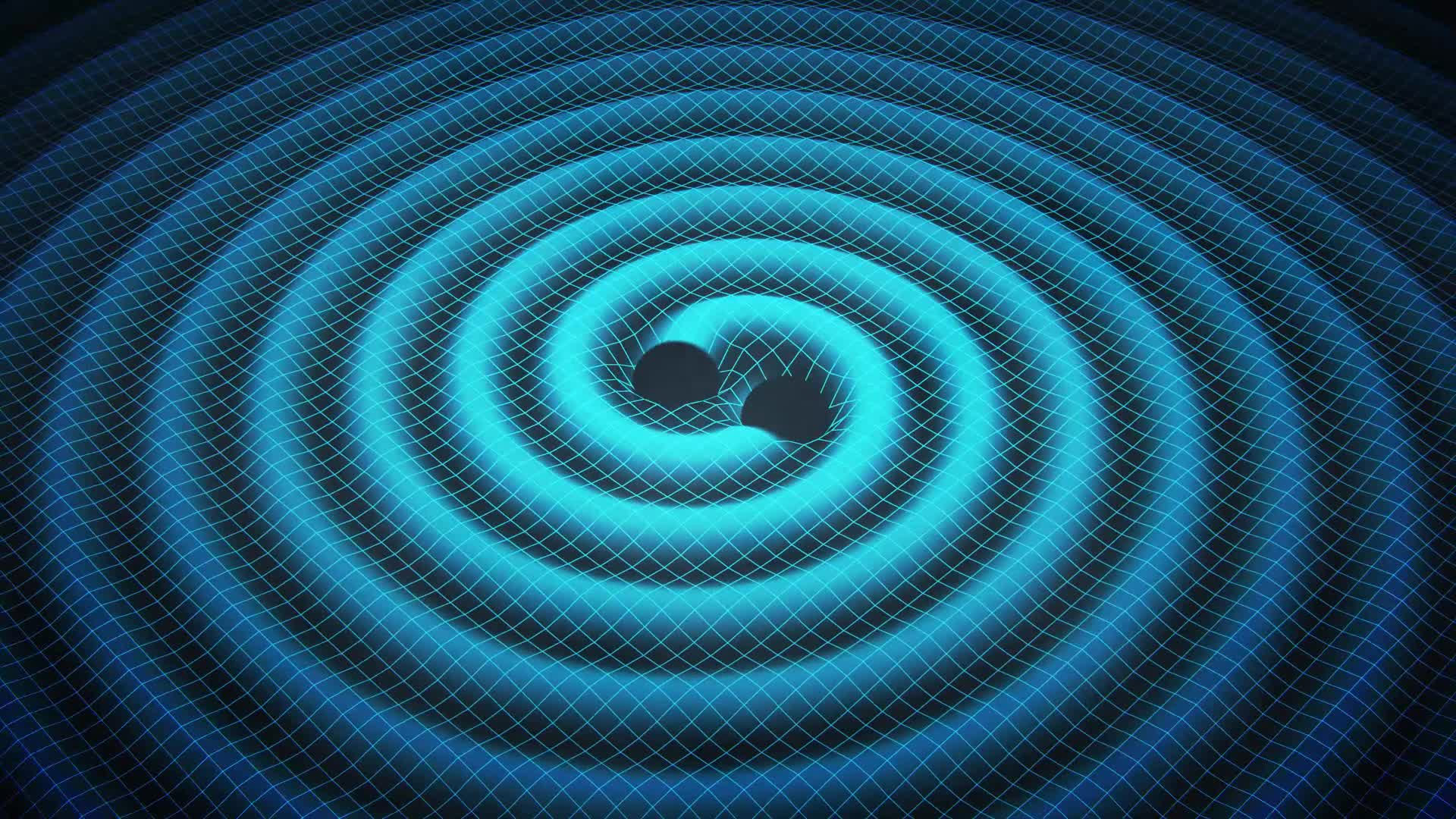

101 years ago, Albert Einstein published his theory of relativity. According to Einstein, orbiting stars that scientists saw spiraling towards each other meant that gravitational waves must have come from those stars. Ever since, scientists have been searching for evidence of gravity waves, which are, in essence, ripples in the fabric of spacetime.

Last Thursday, scientists discovered the first real evidence of gravitational waves, further solidifying Einstein’s theory of relativity and many scientists after him. One of those scientists is Dr. Neil Comins, Professor at the University of Maine.

“I began doing research on gravitational waves in 1974 at the University of Maryland, shortly after I graduated from Cornell,” Comins said. “I worked for Joe Weber at MD, who had built the first generation of gravitational wave detectors.”

After helping Weber with the first generation of wave detectors and having a hand in the designing of the second generation wave detectors, Comins was unsatisfied with the sensitivity of these machines to detect what was needed. Comins then enrolled at University College in Cardiff, Wales to do a Ph.D. on the theory of gravitational waves.

Comins describes gravitational waves by pulling and relaxing an elastic fabric.

“This alternating expanding and contracting is what space does as gravitational waves travel through it.,” Comins said. “By the way, they are extremely tiny, which is why it is hard to detect gravitational radiation. As one goes by, every inch is expanded or contracted by less than a thousandth of a billionth of a billionth of an inch.”

“The first talk I ever gave on my work was to Stephen Hawking and his research group at Cambridge University,” said Comins. “Hawking expressed support in what I was doing.”

The February 11th discovery was the first detection of gravitational waves by seeing the ripples pass by wave detectors, one in Louisiana and the other in Washington state.

“The new results directly confirm the existence of gravitational waves and hence support the predictions of Einstein’s general relativity,” Comins said. “Prior to these observations, we only knew of gravitational waves indirectly, namely we saw orbiting stars spiraling toward each other and according to Einstein’s theory of General Relativity, that meant that gravitational waves must have radiated out from those stars.”

Comins moved to Maine because of the ‘way of life’. Teaching astronomy, which includes general relativity and gravitational waves, and physics at UMaine, Comins is excited about the new findings even though he is not researching general relativity today.

“This discovery is very important because it supports the scientific community’s belief in Einstein’s general relativity, which we use as the basis of our explanation of how the universe is evolving.”